WHAT IS THE MILLE MIGLIA?

Numerous attempts have been made to answer the question “What exactly is the Mille Miglia?” and the responses have been carefully considered and contemplated. Many of the answers are more than valid, as they involve a Red Arrow race that encompasses a multitude of shades, facets and colors.

Numerous attempts have been made to answer the question “What exactly is the Mille Miglia?” and the responses have been carefully considered and contemplated. Many of the answers are more than valid, as they involve a Red Arrow race that encompasses a multitude of shades, facets and colors.

According to the online encyclopedia known as “Wikipedia”, the Mille Miglia is defined as the following:

“The Mille Miglia was an open-road endurance race which took place in Italy twenty-four times from 1927 to 1957 (thirteen before the war, eleven after 1947). Starting in 1977, the Mille Miglia was revived as a regularity race for vintage cars. Participation was limited to automobiles that were manufactured prior to 1957 and had taken part in the MM historical races. The route was from Brescia to Rome, back and forth. It was the same route as the original race and the starting and finish line were at the very same point on the famous road of Viale Venezia“.

An unobjectionable description, although it doesn’t completely help to elaborate on what the Mille Miglia is exactly, nor does it explain precisely what the race revival is.

In order to better understand the legendary race, it helps to hear two of most famous citations on the Brescian race. In the 50s, Enzo Ferrari, the most eminent figure in the world of auto racing, called the Mille Miglia the “most beautiful race in the world“. It was also Ferrari, otherwise known as the “Drake di Marinello,” who came up with a beautiful description of “a museum in motion, unique and charming, in a beautiful framework of jubilant visitors“while assisting in the race revival in the 80s in Modena.

What is most remarkable is the special “race recipe” that was created in 1982, a lively and bubbly mix of sport, culture, tourism, performances, and international friendships, held in locations that are among Italy’s most artistic and historical gems. It is these places, along with their architectural and natural beauty that made the Mille Miglia become much more than a simple revival but brought the race to an insurmountable dimension.

With its 31st reenactment, the Mille Miglia is the first race in the world, in an eighty-five year time-span, to surpass the number of the editions of the original race. There were 24 historical editions from 1927 to1957 and then from 1958 to 1961 three additional editions in the formula of what is known today as a rally, which included speed stages and long-distance stretches.

Nowadays, the Mille Miglia, in addition to being a spectacular automotive event is a phenomenon that encompasses social and cultural customs, and is considered by those who currently manage it as “a smashing media event”.

In order to comprehend how grand the Mille Miglia event has become in the third millennium, we can take into consideration the numbers that speak for themselves. Simply typing “Miglia Mille” into a search engine like Google brings up 7,530,000 (seven million five hundred thousand) results from all over the world. If we do the same on E-bay, an average of over 9.000 MM objects go on sale every day, which range from model toy cars to book circles selling books, to watches and even stamps. The sellers don’t only come from European countries but also from Australia, the United States, South America, as well as Africa and Asia.

Mille Miglia also has a calling of over 1,500 media correspondents from all over the world, including journalists, photographers and television crew all eager to catch every Mille Miglia edition. These professionals come from 87 different countries and it is thanks to them, that in May of every year, the “most beautiful race in the world” surfaces everywhere: from newspapers to magazines, on television and certainly all over the Internet. 2,500 articles are published annually and normally 384 programes are televised, in over 150 countries around the globe.

In the past, the mere passage of the beautiful race was more than enough to make it famous. Since 1927, half of Italy has been able to simply go to their doorsteps and touch it first hand. There was no need for advertising or the television that didn’t exist. Mille Miglia’s acclaim came about with the beautiful passage of great men and brilliant automotive creations. And the nicest part of all is that no one needed to buy a ticket in order to take part and spread its miraculous energy.

Nowadays one simply cannot miss the Mille Miglia. It is a spectacularly unique and popular celebration that takes places in some of the most striking regions in Italy and attracts millions of individuals from the ages of one to one hundred.

It is such a joyous event, not only given to those who live and work along its 1,600 km route, but to a multitude of fans from around the world that organize their vacations around the race. It is also an event dedicated to the dozens and dozens of school children as well as the elderly, all unified along the sidelines, admiring the fancy cars. They fondly watch the race without concentrating on the collectors’ items in front of them but the wealth of life experiences that are before them. This is a celebration that can also be viewed online. One can find over 8,980 Mille Miglia posts on YouTube.

A museum dedicated to the Mille Miglia has proudly been operating since 2004. And there have been countless articles published on the MM theme. The University of Brescia has created an academic facility (Centro Studi “Mille Miglia: Mobilità e Turismo) that gives their students a chance to deepen their knowledge of the race and its connections to tourism and mobility. Plenty of students have graduated and dedicated their research and thesis to the Mille Miglia. The scope behind the new research facility is to develop and support a university curriculum dedicated to the “Economics of Tourism”.

Nowadays, the Red Arrow logo represents an international brand, thanks to the numerous commercial licenses agreement, including the one that immediately comes to mind for Chopard watches. It has become a “must” on every continent.

For the millions of fans dispersed in every corner of the world, the Mille Miglia represents more than anything else, a way of life. Fortunately this unique lifestyle is an extraordinary means of opening doors not only for Brescia but also for Italy as a whole.

Every year 380 crews from over 30 countries around the globe participate in the reenactment of the historical race. Over the years, individuals from 50 different countries around the world have participated in this alluring race.

“Look at this square and go around the city, as you will discover just how much the Red Arrow has become a cultural, economic and sporting gem for Brescia in the world. It is an event that cannot be told, one must actually live it in order to taste it to its fullest. It is a pathway to a regularity competition that gives the utmost joy to those that participate”.

Brescia, Piazza della Vittoria, 1996.

Beppe Lucchini, one of the promoters of the Mille Miglia reenactment.

HOW TO PARTICIPATE IN THE MILLE MIGLIA & TRY TO WIN IT

The irresistible charm that made Mille Miglia the “most beautiful race in the world” – formerly as a speed race, and more as a regularity race – has an enchanting appeal for thousands of fans who hope one day to be able to take that long ride down Italy. What not everybody knows is that race participation is strictly regulated. In order to make these rules clear, we wish to illustrate the 1000 Miglia Regulations, both in terms of the car characteristics permitted as well as how placements are determined.

AUTOMOBILES ADMITTED

In order to avoid misunderstandings, we wish to point out that ther’s more than the mere possession of a vintage car involved.

The only automobiles departing from the famous ramp on Viale Venezia are those produced during the historical Mille Miglia years, from 1927 to 1957.

This refers to racing cars, in other words, those that make up the “Sport” category, or automobiles with identical characteristics to those touring cars that took part in the Mille Miglia “Touring” or “Grand Touring” categories in one of the twenty-four historical race editions.

Obviously, the selection process will give precedence to cars with a proven track record, such as those who have appeared on Palmares Winner’s Lists or have taken part in a Mille Miglia historical race. To get a better idea of the type of car admitted we could use the 1955 MM winner as an example. It was a 300 SLR, a vehicle that Mercedes-Benz brings to Italy every year from its Stuttgart Museum collection.

Under no circumstances will automobiles built after 1957 be considered for entry. However, some special vehicles, produced in the early twenties and participants in early races, may be considered for entry. It is important to bear in mind that all vehicles admitted will be rigorously checked to ensure that every single part of the automobile is authentic.

In order to avoid any attempt at entering altered vehicles, all cars must comply with the FIVA (Federation Internationale Voitures Anciennes) regulations and hold the proper FIVA International Identity Card, otherwise known as the “FIVA passport.”

This FIVA ID card serves as proof that the vehicle being presented is in its original form. To obtain this document, the vehicle must undergo “verification tests” by the appropriate Board of National Federated Clubs. In Italy, the organization responsible for verifying that vehicles are original is known as ASI (Automotoclub Storico Italiano) or “Italian Historical Automotive Club”.

A process known as “Scrutineering” is done on all vehicles prior to the MM race. The purpose of scrutineering is to do pre-event checks of all the aforementioned documents as well as perform other checks including verification of periodic roadworthiness tests required by the Highway Code.

COMPETITOR’S DOCUMENTS

In addition to technical checks, the competitors must undergo additional checks: the two drivers must shows valid automobile insurance, their driving licenses and the driver must show a C.S.A.I. (Commissione Sportiva Automobilistica Italiana) regularity license as well. Foreign competitors must hold a “Green Card” or what is known as an International Motor Insurance Card and also show, or obtain, a valid sport license prior to departure.

THE COEFFICIENTS

Cars will be attributed a coefficient which will take into consideration the period of the car’s design and construction as well as the diverse technical characteristics and capabilities of the varieties of sport and classic cars in the race.

The coefficient acknowledges the fact that there are profound differences between a car built in the twenties and one from the late fifties, and between a racecar and a comfortable Grand Touring vehicle. It also takes into account the various differences in driving the actual car. Consider, for example, the difference between drum brakes with external levers from the twenties and disc pedal-controlled brakes from 1956/1957. The basic principle behind the coefficient is that the older cars and cars that are more of sports cars are assigned the highest coefficients.

Moreover, the coefficient can be increased in the event that a car has a historical relevance, such as those cars that have won a Mille Miglia historical race. A bonus will be assigned to automobiles that have participated in one of the twenty-four editions of the Mille Miglia speed races.

The crew with the highest number of points will win. In practical terms, the ranking is the sum of points obtained by each crew during the regularity race multiplied by the coefficient assigned to the vehicle. Therefore, the higher the ratio, the more likely one is to win. Let’s bear in mind, however, that it takes much more than just the car itself to win…

THE AWARDS

The awards, just as the regulations indicate, are symbolic, and exclude monetary prizes. In reality, it is quite evident that the Mille Miglia really excels in all things: the Mille Miglia cups assigned to the winners, differently from other vintage car races, are exact reproductions, in sterling silver, of the Mille Miglia Cups from the fifties.

THE CHRONOMETERS AND ROAD BOOK: THE PRINCIPLES BEHIND THE REGULARITY RACE

The most frequently asked question is: if the fastest car doesn’t win, what exactly does it take to win the Mille Miglia? To understand the workings of the regularity race better, the “Mille Miglia Race Regulations” can be consulted.

The basic principle behind speed races as compared to regularity races is rather simple: in the latter, it is necessary to respect pre-established “target” times rather than finishing the race as quickly as possible; arriving at the finish line earlier or later does not make the difference. In both cases the competitor will be penalized.

In a regularity races, cars are normally classified according to three criteria: Time Controls, otherwise known as “C.O.”, Passage Controls, known as “C.T.” “Regularity Stages”, otherwise called “P.C.”, which are the same as what is known as “special stages” in a rally.

The Time Controls or “C.O.” indicates the times in which the competitors need to reach pre-established points: they serve in uniting groups of cars, and are placed on long-distances stretches of several hours. Vehicles receive penalty points based on the minutes of error over or under the established time.

The Passage Controls or “C.T.” serve the purpose of preventing competitors from cutting the route short. Competitors are obliged to get stamps at the passage controls indicated by the race organizers.

There are approximately seventy regularity stages in the Mille Miglia, which serve as determiners of how cars are later ranked in the race. Race regulations require cars to race along a segment of a route – normally either closed or distant from traffic – maintaining a “target” pace. For example, a “Regularity” Stage or “PC” of 3km could have a given time of 0:3 ’36 “, that is, three minutes and thirty seconds. For every hundredth of a second error, above or below the precise “target” time, the competitor receives a penalty. The winner of the regularity stage is the one with the least penalties.

In Mille Miglia, but not in other races, the result of each regularity stage is given a point value: the winner is the one with the highest score (after the appropriate coefficient has been applied).

From a practical point of view, things develop in the following manner: Timekeepers synchronize the chronometers that are connected to two pressure switches (rubber tubes placed at the departure and arrival points, which trigger the timer when pressed by the front wheels of the vehicle), and positioned at the beginning and end of each regularity stage or “PC”.

As racecars pass, the printers connected to the timers faithfully record the times cars take to complete regularity stages and record any differences; ahead or behind of the established time. For every hundredth of a second difference over or under the “target time” a penalty is imposed.

It is important to point out that the champions, or those that CSAI classify as “Top Drivers” often manage to complete a regularity stage obtaining a perfect transition to the hundredth of a second, with zero penalties. They tend to remain within the range of eight or nine one-hundredths of a second as their maximum error. Good drivers tend not to exceed errors of more than fifteen one-hundredths of a second.

Normally, a race is won with an average error between two and three one-hundredths of a second. Being that the Mille Miglia is quite long and difficult, those averages go up a bit, and everything is rendered more complicated due to the application of coefficients.

All the particulars of the Mille Miglia route, as well as the Time Controls, Passage Controls and Regularity Stages can be found in the “road book” along with precise notes on average times and speeds to be followed and distances to be traveled.

APPARATUS AND AVERAGE SPEEDS

In order to meet the target times imposed, drivers and co-drivers use an apparatus, which is in fact a small computer, equipped with all the necessary timers. In practice, the entire race timetable, including all time controls and imposed target times for regularity stages have all been determined prior to the race. During the race, at a given checkpoint or at the “pressure check” prior to a regularity stage, the driver (the champions prefer to do this themselves) merely presses a button that starts or stops the time. To ease the transition, these devices emit a countdown “beep”, which every driver sets as he wishes for the last ten, five or three seconds, of a stage. If you should see a driver with earphones, it is not because he is listening to music on his iPod, but gauging the seconds remaining to the end of his regularity stage.

These time gauges count down the seconds remaining and serve to assist the driver in seeing whether he is maintaining the proper speed on the stretch of the road he is traversing.

They work even better when linked to the GPS – Trip Master, becoming an extremely high-tech kilometer counter (calibrated each time with utmost precision at the beginning of the stretch), and can be separately reset for Time Controls and for Regularity Stages. One of the most important rules of the regularity race is the maintenance of a steady speed along the route. The C.S.A.I. (Commissione Sportiva Automobilistica Italiana) that oversees all of the Italian automotive races, imposes a speed of no more than 40 km/h, or 50 km/h on flat stretches for races involving classic cars.

To a layman these speeds may seem rather slow and not particularly appropriate for a race. Yet these speeds are everything but that, as we need to take into consideration that with the exception of speed trials, the entire route is open to traffic, time is lost while traversing historical city centers, as well as for refueling and maintenance. Bear in mind that the most recent car in the race is at least fifty years old, so we can certainly define these speeds as “racing speeds.” Just to give an idea, the classic car “Topolino”, and other low cylinder cars very often get to the finish line at a speed above the maximum. The important thing is to never stop, or at least to stop as little as possible.

So these are the basic rules on how to win – in addition to having natural talent and the right car – one needs lots and lots of dedication and commitment. Just as all of those who have raced the Mille Miglia can confirm, what is more important than the victories, or let’s say one of the most profound joys one can feel – is to see the crowds that await you after 1600 km – all of them cheering at the finish line in Viale Venezia, Brescia.

LOCATIONS TRAVERSED BY THE MILLE MIGLIA

1927/1957: NUMBERS AND YEARS

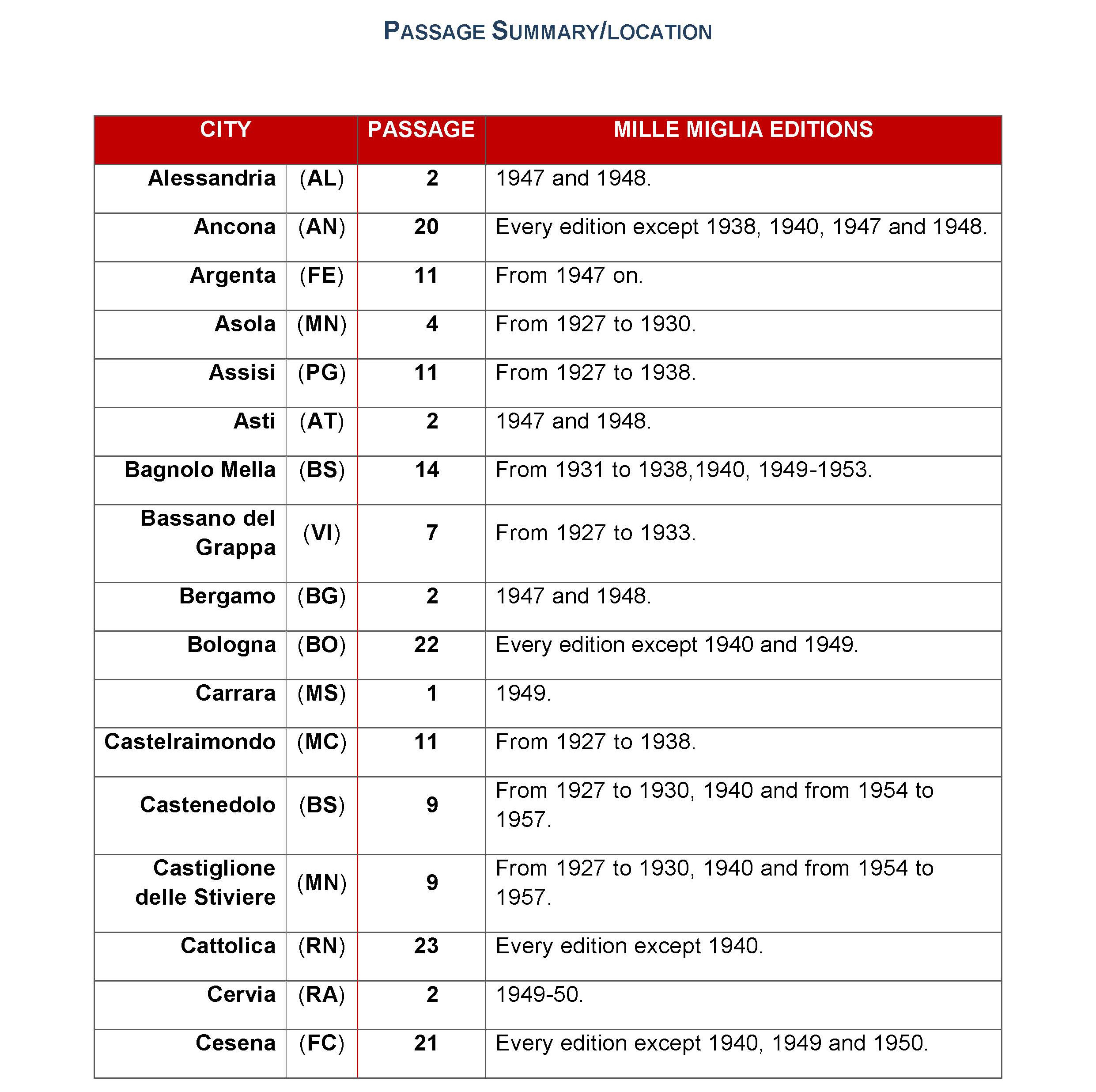

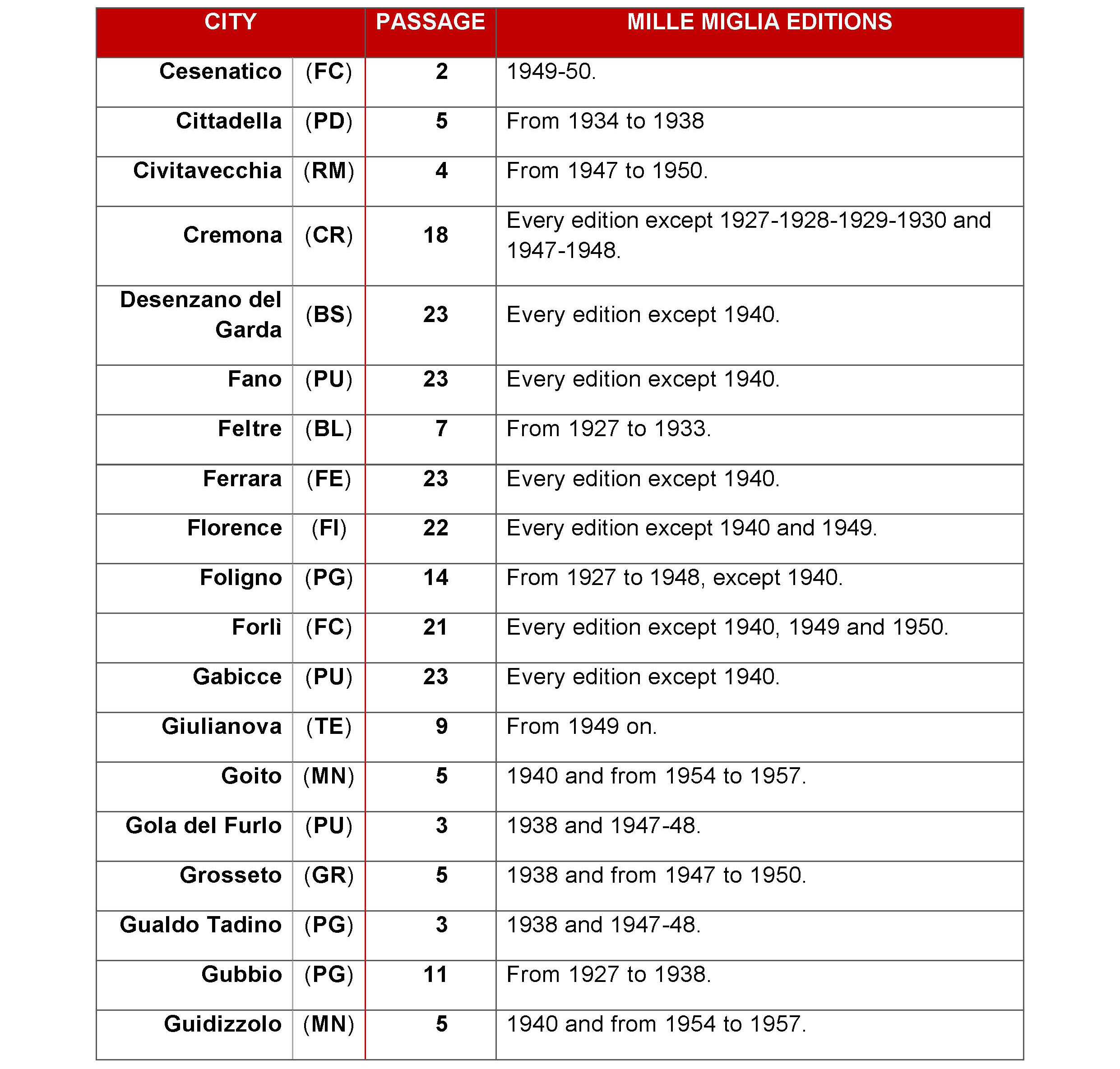

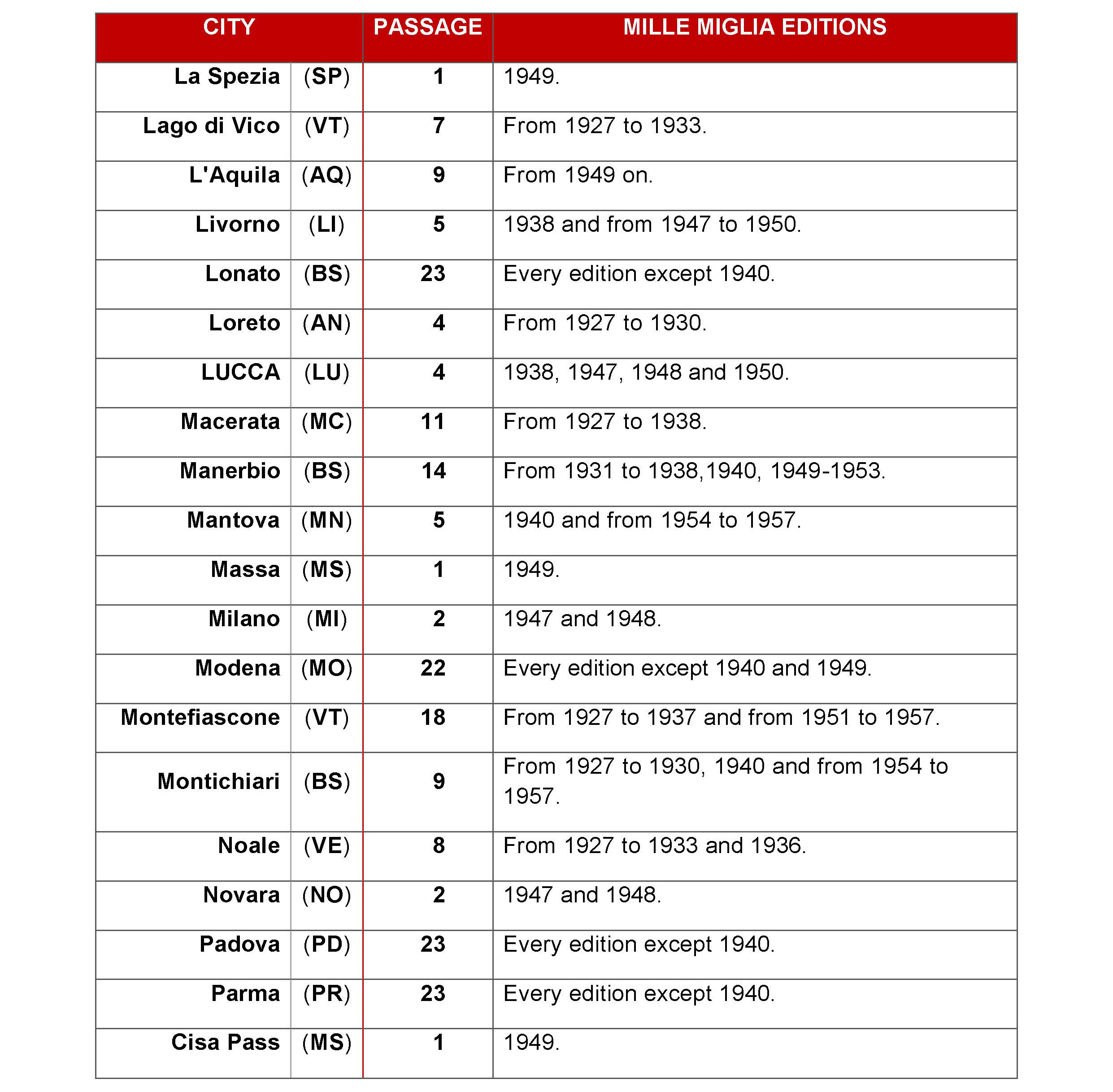

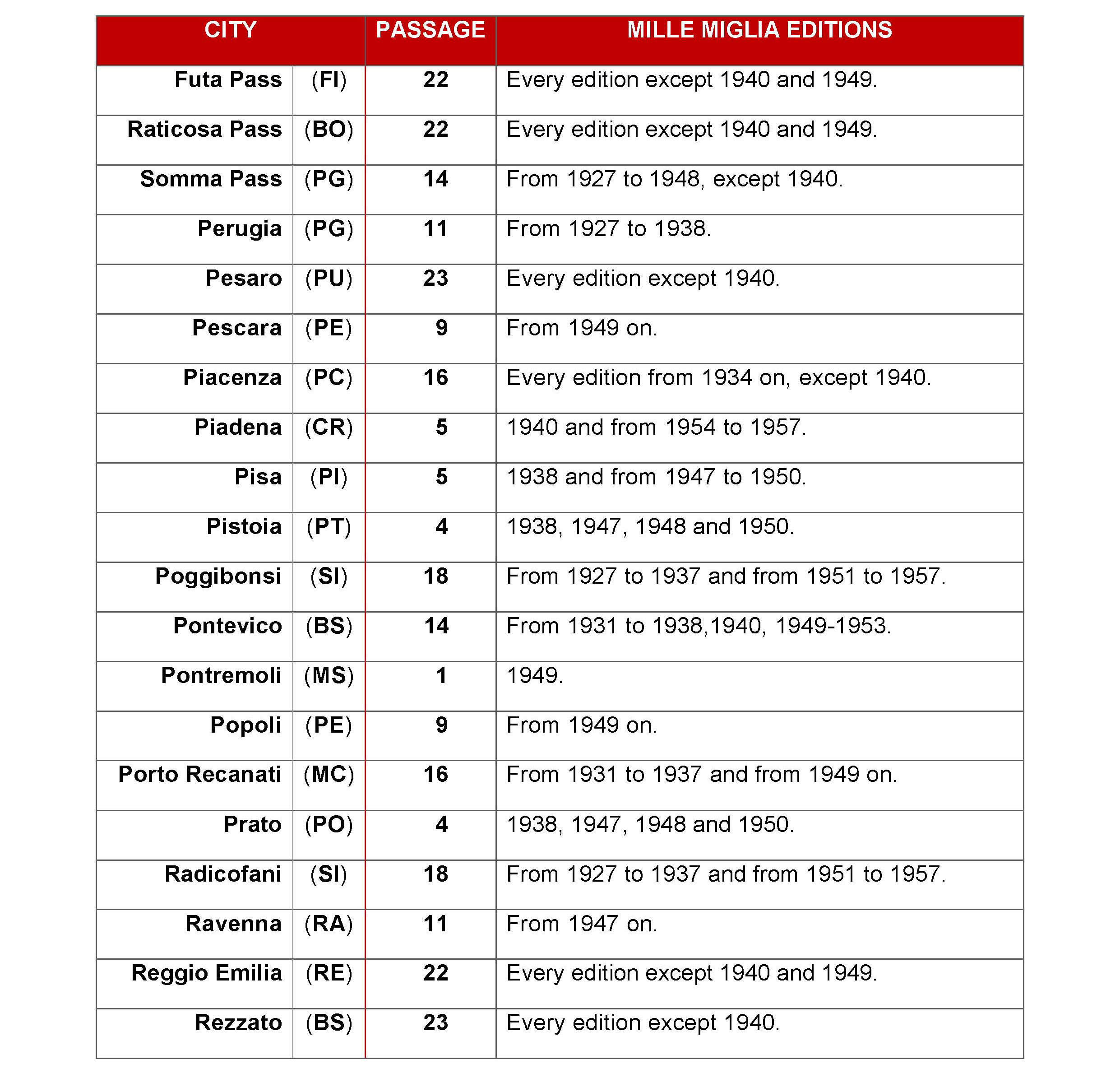

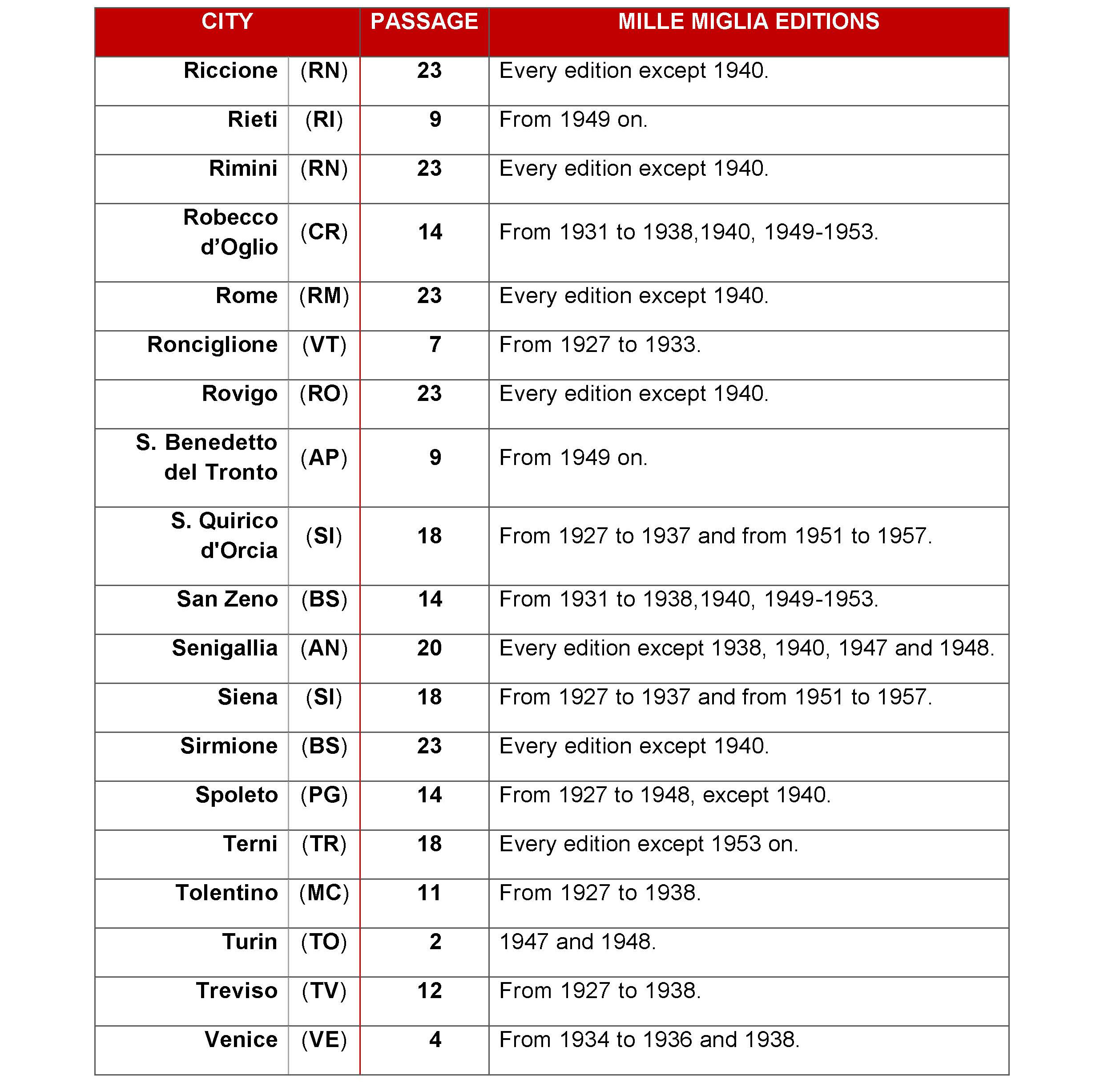

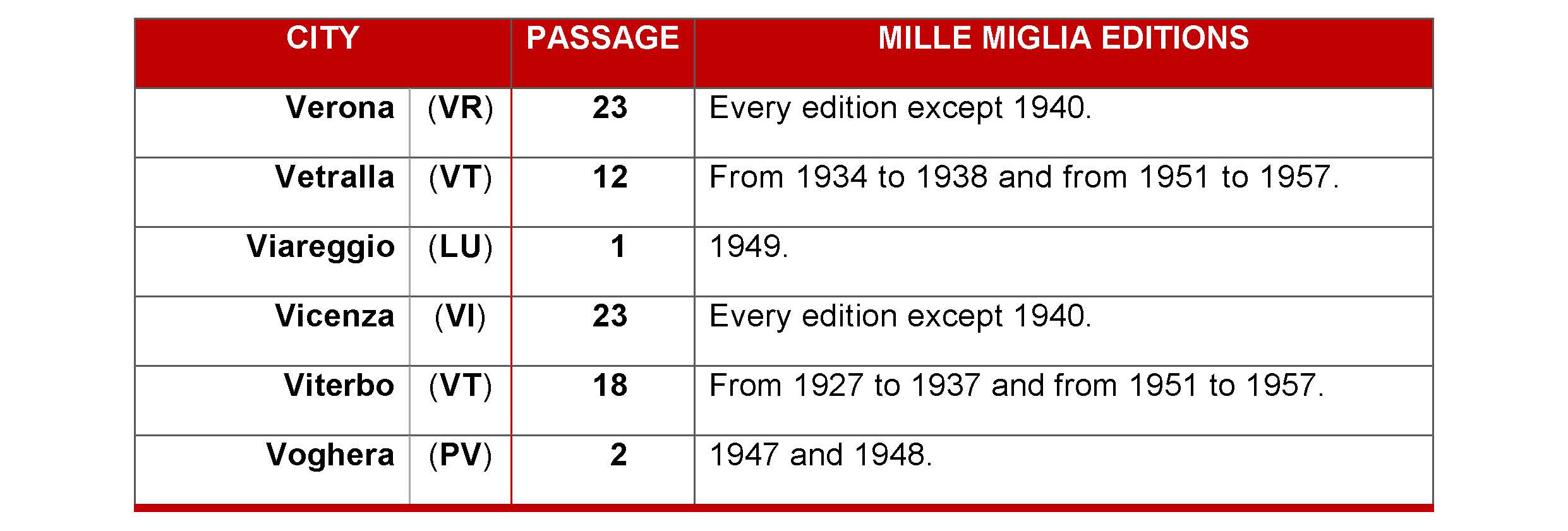

The statistical research was carried out, by comparing the twelve different racecourses from each of the twenty-four editions of the Mille Miglia race, from 1927 to 1957.

It must be noted that, in 1940, an anomalous edition was disputed: the Gran Prix Brescia Mille Miglia, on the closed circuit, Brescia-Cremona-Mantova-Brescia, to be lapped nine times (eight times for those vehicles of classe 1.100 cm3).

Mention of the city’s name indicates where the passage took place in that region.

LOCATION ALONG THE RACECOURSE OF THE 24 MILLE MIGLIA:

The only City –understood to be within City limits – involved in all twenty-four editions, was Brescia, who boasts twenty-three start and finishes from Viale Venezia and one start and finish from Viale Duca degli Abruzzi, in 1940, for the Gran Prix Brescia Mille Miglia.

No other city within the Brescia Province can boast twenty-four transits.

- 23 PASSAGES:

Rome, Parma, Pesaro, Fano, Rimini, Riccione, Gabicce, Cattolica, Ferrara, Rovigo, Padova, Vicenza, Verona, Rezzato, Lonato, Desenzano del Garda, Sirmione and Peschiera del Garda: every edition except 1940.

- 22 PASSAGES:

Reggio Emilia, Modena, Bologna, Futa and Raticosa Pass, Florence: every edition except 1940 and 1949.

- 21 PASSAGES:

Forlì and Cesena: every edition except 1940, 1949 and 1950.

- 20 PASSAGES:

Ancona and Senigallia: every edition except 1938, 1940, 1947 and 1948.

- 18 PASSAGES:

Terni: every edition from 1953 on. Cremona: from 1931 to 1938, 1940 and from 1949 to 1957. Viterbo, Radicofani, S. Quirico d’Orcia, Siena, Poggibonsi: from 1927 to 1937 and from 1951 to 1957.

- 16 PASSAGES:

Piacenza: every edition from 1934 on, except 1940. Porto Recanati: from 1931 to 1937 and from 1949 on.

- 14 PASSAGES:

Foligno, Spoleto, Somma Pass: from 1927 to 1948, except 1940. Robecco d’Oglio, Pontevico, Manerbio, Bagnolo Mella and San Zeno: from 1931 to 1938, 1940 and from 1949 to 1953.

- 12 PASSAGES:

Treviso: from 1927 to 1938. Vetralla: from 1934 to 1938 and from 1951 to 1957.

- 11 PASSAGES:

Assisi, Perugia, Gubbio, Castelraimondo, Tolentino and Macerata: from 1927 to 1937. Ravenna: from 1947 on.

- 9 PASSAGES:

Rieti, L’Aquila, Popoli, Pescara, Giulianova and S. Benedetto del Tronto: from 1949 on. Castiglione delle Stiviere, Montichiari, Castenedolo: from 1927 to 1930, 1940 and from 1954 to 1957.

- 8 PASSAGES:

Noale: from 1927 to 1933 and 1936.

- 7 PASSAGES:

Feltre and Bassano del Grappa: from 1927 to 1933.

- 5 PASSAGES:

Cittadella: from 1934 to 1938. Piadena, Mantova, Goito and Guidizzolo: 1940 and from 1954 to 1957. Pisa, Livorno and Grosseto: 1938 and from 1947 to 1950.

- 4 PASSAGES:

Lucca, Pistoia and Prato: 1938, 1947, 1948 and 1950. Venice: from 1934 to 1936 and 1938. Civitavecchia: 1947 to 1950. Asola and Loreto, from 1927 to 1930.

- 3 PASSAGES:

Gualdo Tadino and Gola del Furlo: 1938 and from 1947 to 1948.

- 2 PASSAGES:

Cervia and Cesenatico: 1949 and 1950. Voghera, Alessandria, Asti, Turin, Novara, Milan and Bergamo, 1947 and 1948.

- 1 PASSAGE:

Cisa Pass, Pontremoli, La Spezia, Carrara, Massa and Viareggio: 1949.

PROVINCES AFFECTED BY THE RACECOURSE:

The provinces in which the capital cities were not affected by the Mille Miglia were the following: Belluno (from 1927 to 1933), Pistoia and Lucca (on the Firenze-Mare highway, 1947, 1948 and 1950), Pavia and Vercelli (1947 and 1948), Ascoli Piceno and Chieti (from 1949 to 1957).

ITALIAN REGIONS TRAVERSED:

Lombardy, Veneto, Emilia-Romagna, the Marches, Abruzzo, Umbria, Lazio, Tuscany, Liguria and Piedmont.

You must be logged in to post a comment.